Over the course of the 1980s, Taiwan’s per capita income tripled. Exports boomed. The stock market shot up tenfold and looked like it would never come down. The nation’s authoritarian government finally allowed a restless middle class to travel abroad for tourism, not just business or education. The decade saw the final years of martial law, media censorship and political murders, as well as the beginnings of multi-party democracy.

It was a chaotic milieu which blurred freedom and authoritarianism, and in its midst, arts and social movements exploded. The decade is now the subject of a new exhibition at Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), The Wild Eighties: Dawn of a Transdisciplinary Taiwan, which assembles a vast array of more than 700 artworks and artifacts to revisit a decade, which put a bookend to life under military rule and formed a crucible for Taiwan’s free society that we enjoy today.

Early in the exhibition, one encounters photographs of what may have been Taiwan’s first underground art show, Xirang (熙攘), a group show organized in 1986 in the bare concrete cave of an empty building on Zhongxiao East Rd by artist Chen Chieh-jen (陳介仁). A mix of minimalist forms on a concrete floor and low-budget installation art, the exhibition was charged with the trashy frisson of a salon des refuses by artists, who, the curators tell us, were out to “protest against art museums, commercial galleries and other institutionalized art formats.” Did they have an inkling that martial law would end less than two years later? For nothing short of pure freedom would do!

Photo courtesy of TFAM

‘LIVING CLAY’

Xirang literally translates as “living clay,” an idea which head curator and TFAM director Wang Jun-jieh (王俊傑, also an exhibitor at that first Xirang exhibition) expounds into the concept of terra genesis, the ground from which all things spring. This is Wang’s grand metaphor for the 1980s and their seminal importance to post-martial-law Taiwan. Wang curated the exhibition together with Huang Chien-hung (黃捷宏) and a research team from Taipei National University of the Arts.

Xirang, perhaps not incidentally, was also the name of one of Taipei’s first rock ‘n’ roll live houses in the late 1980s. (It is not featured in the exhibition.)

Photo courtesy of TFAM

Upon entering the first gallery, one is greeted by a row of five magazines (Echo, Lion’s Art Monthly, and Formosa Magazine), a forewarning of Wild Eighties’ heavy literary basis. Huge numbers of magazines, books, newspaper clippings and other documents are distributed through the galleries, which often resemble bookstore displays. The printed materials are both a testament to the explosion in free speech as well as to the exhibition’s bias towards defining Taiwanese society according to intellectual discourse.

Exhibition sections specifically examine avant-garde art movements, politics, foreign influences, cultural identity and the synthesis of all these things within a post-martial-law Taiwanese society, here envisioned as a sort of inchoate blob.

“Everything was interconnected, and kept congregating, circulating and changing,” write curators Wang and Huang.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

In the arts, experimental theater, modern dance, installation and performance art, and rock ‘n’ roll were finally free to sprout through the cracks of a crumbling authoritarian edifice. The island’s first experimental theater festival was organized by director Yao Yi-wei (姚一葦) as early as 1980. Choreographer Lin Hwai-min (林懷民) developed the Martha Graham technique in his Cloud Gate Dance Troupe (雲門舞集). Lo Ta-yu (羅大佑) emerged as the nation’s first rock star, singing on behalf of small-town Taiwan, daring to criticize the government and recording his second album with a backing band of foreigners, including Taipei American School students and alumni.

One frequent motif in performance arts is naked, rope-bound bodies, sometimes screaming in mock agony, a protest against life as anonymous subjects of control. These figures jump out at you in The Cowardice of Intellectuals (1984), a video art work by Chen Chieh-jen, and several experimental theater pieces like Wang Mo-ling’s “Body Theory.” Restored VHS video recordings offer a fascinating glimpse of period theater productions.

The curators define this new “avant-garde” impulse as the collision of “local conditions” and “foreign information,” with an emphasis on original Taiwanese creations over massive foreign pop culture inputs, including a gargantuan pirate book and music industries, which ended in the late-1980s under threat of US intellectual property sanctions.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

At the same time, the 1980s saw seeds of every type of social movement begin to sprout — farm and labor rights, feminism, queer rights, multi-ethnic identity and the anti-nuke movement — here exhibited as documentary photographs, printed matter and explanatory captions. In 1986, Chi Chia-wei (祁家威) became the first Taiwanese to publicly come out of the closet. We see early feminist writings by Annette Lu (呂秀蓮), Taiwan’s vice president from 2000-2008. From 1986, the Green Team (綠色小組) wielded the new technology of consumer video cameras to document nearly every social movement of the era, sowing the seeds of Taiwan’s alternative media.

New official institutions also appeared. The Taipei Fine Arts Museum opened Christmas Eve 1983, a design of minimalist, stacked square tubes constructed on ground formerly occupied by US military housing. Its mission, as reported in a China Post newspaper article, is to “provide leadership in the arts so as to contribute to the spiritual understanding of Free China.”

The Golden Harvest Film Festival launched in 1978 to promote short and experimental films. Early award winners included now-famed directors Ang Lee (李安) and Tsai Ming-liang (蔡明亮).

The exhibition’s strength and weakness is its vast profusion of raw data — objects, timelines, even a map of Taipei venues for underground culture. These will speak to Taiwanese who lived through the 1980s, but the presentation is based on the annoyingly common assumption in Taiwan of “everybody knows,” which is to say that extremely local histories will be universally and automatically understood. Non-Taiwanese visitors may be underwhelmed by the lack of context.

The map of underground venues includes my personal favorite 80s fragment in the show, a promo video for Taiwan’s first legal, large-scale disco, Kiss La Boca (located in the basement of what is now the Mandarin Oriental Hotel on Taipei’s Tunhua North Rd — and yes, I’ve been there). Kiss La Boca’s giant room of screaming, dancing Taiwanese, intercut with quick clips of foreign performers from male burlesque to Stevie Wonder, was perhaps the real revolution of Taiwan in the 1980s. The video is a refreshing break from the all text-heavy discourse.

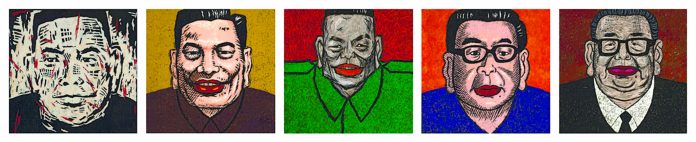

The exhibition ends with yet another room of magazines — by this point I was too tired to parse them — above which hang a series of five large portraits of Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國, president 1978-1988). The Five Phases of President Chiang was painted by Wu Tien-chang (吳天章) in 1989, just a year after the leader’s death. Such stylized, almost political cartoon-like portraiture could not have been allowed while Chiang was still alive.

The images range from the military bearing of a neo-Stalinist cadre to the humble mein of an aging, bespectacled official. They seem to be almost different men, and they embody the contradictions of the man himself — the China-born son of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), educated in the Communist academies of Stalin’s Russia, the architect of Taiwan’s White Terror, custodian of Taiwan’s economic miracle in the 1970s and 1980s and ultimately the man who dismantled his own secret police force and ended 38 years of martial law. Chiang’s is a conflicted legacy to be sure, a perfect paradox, just like Taiwan in the 1980s.

What place in Taipei is universally acknowledged in tourism sites, in the media and among the denizens of the Celestial Dragon Kingdom (天龍國) as one of Taiwan’s premier historical and shopping areas, attracting millions of visitors each month? Ximending (西門町), of course. Its superlative success is based entirely on restricted vehicle access. As a pedestrian zone, Ximending has been transformed into a shopping mecca. Yet, weirdly, the cities outside of Taipei all have MRT-envy, when they could be emulating Ximending. The pedestrian zone has been so popular that in 2008, as development elsewhere in the city drew shoppers away, it

Down in the southernmost reaches of Taiwan, the Neiwen River (內文溪) forms from headwaters just three kilometers from the Pacific coast. But due to the lopsided terrain of the Hengchun Peninsula, the river winds westward from here toward the Taiwan Strait, over 20km away on the opposite side of the island. Along the way, it takes a sudden drop at Shuangliu Waterfall and several smaller drops at check dams lower down. Eager tourists snap photos, egrets fish in its waters and children splash around to cool off. Finally, the river meets the Daren River (達仁溪) to form the Fenggang River (楓港溪)

Dec. 12 to Dec. 18 Lien Jih-ching (連日清) had many monikers during his life, but his daughter’s favorite is “Mosquito Man” (蚊人), which sounds similar to the Mandarin word for “literati.” “He studied mosquitoes at work, cared for them after he got home and his hobby was collecting specimens,” Lien Hsiu-mei (連秀美) writes in her 2007 biography of her father. “Nobody understands mosquitoes better than he does … He even knows what they’re thinking.” Despite contracting an excruciating bout of dengue fever during his first mosquito collecting expedition at the age of 15, Lien eventually made it his life’s work to study them

In his Pensees, published posthumously in 1670, the French philosopher Blaise Pascal appeared to establish a foolproof argument for religious commitment, which he saw as a kind of bet. If the existence of God was even minutely possible, he claimed, then the potential gain was so huge — an “eternity of life and happiness” — that taking the leap of faith was the mathematically rational choice. Pascal’s wager implicitly assumes that religion has no benefits in the real world, but some sacrifices. But what if there were evidence that faith could also contribute to better wellbeing? Scientific studies suggest this is