ADVERTISEMENT

REVIEW: 'Grace' by Cody Keenan

SHARE

Remember Barack Obama, the cocksure memoirist who ran for president to pad his résumé and went on to solve racism and restore peace on earth? The guy whose soaring rhetoric sent thrills of ecstasy coursing through the inner thighs of veteran journalists and millions of American voters who could finally prove to the world they weren’t racist?

That was a different time, back when John Boehner and Mitt Romney were considered existential threats to democracy. When the people in charge of deciding such things decided the white dorks who helped Obama write his speeches would be treated like actual celebrities.

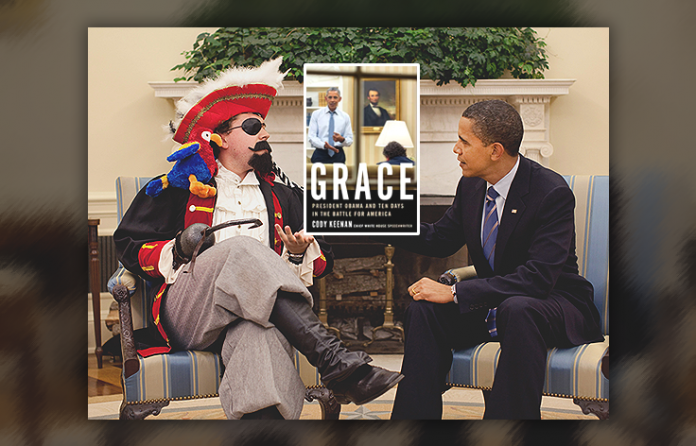

One of those white dorks has written a book about what it was like. Grace by Cody Keenan, the top White House speechwriter during Obama’s second term, is a “behind-the-scenes drama” encompassing a 10-day period in 2015 during which the wunderkind author and his genius boss “composed a series of high-stakes speeches” that changed the world or whatever.

The book is as overwrought and tediously verbose as an Obama speech, describing utensils that “blared patriotic merriment” and the “cobalt, maybe sapphire” color of the president’s tie. Riddled with adjectives and synonyms. Written by a Writer. Keenan, best known for wearing a pirate costume to make fun of Fox News, recounts his noble struggle to prepare speeches for momentous Supreme Court rulings on Obamacare and gay marriage, as well as a eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, the pastor murdered by a racist coward along with eight others at a church in Charleston, S.C.

The story eventually culminates in a viral moment the average voter might vaguely remember seeing on Facebook or YouTube. The time Obama sang “Amazing Grace” at the pastor’s funeral. It is regarded by people who regard such things as the “most famous” of the 44th president’s speeches. And it almost didn’t happen. Obama didn’t want to give the eulogy until Valerie Jarrett ordered him to do it. Keenan didn’t want to write it because of time constraints and white guilt and imposter syndrome. Grace is intended for people who find this “drama” compelling.

The way Keenan describes it, being Obama’s top speechwriter was a living hell. Overworked and underslept, the author would twist himself into “pretzels of self-loathing” in the “jaundiced fluorescence” of his basement office while “sitting alone at a computer, bereft of sunlight, freaking out about what to write, stewing in a toxic mix of pressure, stress, and self-doubt.” Keenan “ruined three consecutive Christmases” by obsessing over a State of the Union address no one cares about. He wound up at Walter Reed hospital with an irregular heartbeat and hypertension. Even the celebrity aspect was annoying, with reporters pestering his family members for details about his life.

Nevertheless, he persisted, driven by the “fear of failing” his boss, the globally significant orator who could “turn the text into a script, a sheet of music, a piece of American art on display in a striking scene.” That’s what made working for Obama so “fucking terrifying,” Keenan explains. The self-proclaimed “better speechwriter than my speechwriters” would politely assess his drafts—”well-written, but…”—before striking 12 paragraphs and replacing them with 30 new ones to create “a beautiful emotional nexus” that could “change people’s thinking about America and its possibilities.” (This was before Smart Brevity™ was invented.)

That’s one way of assessing Obama’s talent for persuasion. This was certainly the prevailing view at the time among the already persuaded journalists and elite professionals whose views tended to prevail. Obama’s extreme arrogance wasn’t bizarre, it was justified. He deserved that Nobel Peace Prize. His speeches didn’t just change minds, they changed history. It’s jarring to revisit years later, when Obama’s aura of messianic invincibility has faded considerably. Even his former admirers are starting to wonder whether the incessant speechmaking was a tad self-indulgent, a vehicle for Obama to show off and help liberals feel good about themselves.

Keenan describes his like-minded White House colleagues as if pitching a reboot of The West Wing, the obnoxiously idealistic TV series that inspired an entire generation of privileged nerds to go into politics and make a difference. These are the people who staffed Obama’s administration.

Chief of staff Denis McDonough is “a library of folksy metaphors.” Communications director Jen Psaki is a “whip-smart, flame-haired” “bolt of cheer.” Press secretary Josh Earnest has “an unguarded smile and a very un-Washington willingness to reveal boyish wonder at a new discovery.” Senior adviser Dan Pfeiffer is “deeply thoughtful, mildly sardonic, and well liked” with an “encyclopedic knowledge of rap.”

Keenan’s assistant Susannah Jacobs “practically burst with a hopefulness to the point where you wanted to protect her from the world breaking her heart.” His team of speechwriters saw their jobs “not as the pinnacle of a career but as a platform to help make a positive difference in people’s lives.” Ben Rhodes, the mullah whisperer, appears every so often to bump fists, drop F-bombs, and intimidate subordinates with his “seen-it-all demeanor.”

The author’s fiancée at the time, a White House fact-checker who turned him down three times before he got promoted, delivers the book’s most poignant line. “Everyone here is beyond words,” she tells him after Obama’s eulogy in Charleston. “Today is the most West Wing day of all the days.” Keenan was getting drunk on Air Force One, relieved to be done after spending the last few nights in sleepless agony.

After all, he was just another “white man who thought he was on the right side of things [but] still had a lot to learn.” Raised in the wealthy suburbs of Chicago and New York, educated at Northwestern and Harvard. A man without faith, he learned about hardship by spending his summers in the public library reading The Color Purple. How could he possibly write a eulogy for a murdered black pastor, to be delivered by the country’s first black president? A speech about grace and forgiveness that didn’t merely honor the deceased, but exploited the bully pulpit to strike “a blow against injustice … for a better America”?

He didn’t, really. Obama rewrote the speech almost entirely, doubling its length in the process. And the rest is history, at least for those who still believe the West Wing propaganda. (A far more reality-based portrayal of our political system can be found in Veep.) The #Resistance scolds who insist, as Keenan does, that “a good chunk of the country” is beyond redemption. Grace is wasted on them. They require penance. They are the only things preventing Democrats from enacting commonsense solutions that would solve our country’s problems and make the world a better place.

The vacuous delusion of our establishment class is epitomized in an email from a CNN producer to Keenan’s predecessor Jon Favreau, the one who dated actress Rashida Jones, several days before the eulogy: “Can the first Black president solve race?”

Alas, he could not.

Grace: President Obama and Ten Days in the Battle for America

by Cody Keenan

Mariner Books, 320 pp., $29.99

Published under: Barack Obama, Book reviews

2022 All Rights Reserved