Advertisement

Supported by

The state is distributing 5,100 new body-worn cameras, the most extensive commitment of any state as corrections facilities across the country push for better surveillance.

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

Thousands of Ohio prison guards will begin wearing body cameras for the first time this year, bringing more transparency inside prison walls at a time when the coronavirus pandemic and guard shortages are making many prisons more dangerous.

Annette Chambers-Smith, the head of the state prison agency, said the state was buying 5,100 body-worn cameras that will be used by guards and parole officers in all of the state’s prisons. Not every guard will wear a camera at all times, but the program is still ambitious: Axon, the company that is supplying the cameras, said the state was adopting the largest body camera program of any prison agency in the world.

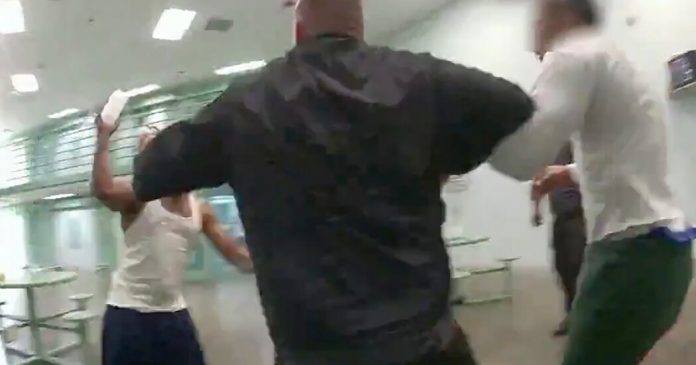

There are already thousands of surveillance cameras across Ohio’s 28 state prisons, but the addition of body cameras could make it easier to review the actions of guards and prisoners, capturing incidents that are not visible through existing cameras or are blocked from view by other people.

The move comes as several other states have begun to use body cameras in prisons and jails, albeit on a smaller scale, amid increasing criticism that prison guards, like police officers, are regularly involved in violent encounters that may involve witnesses with competing versions of events.

“This is ultimately about safety, transparency and accountability for everyone who works or lives in our prisons,” Ms. Chambers-Smith said in a statement.

The plan to roll out body cameras follows the death in January of last year of Michael A. McDaniel, a 55-year-old prisoner who collapsed and died after guards pushed him to the ground several times following a fight outside of his cell. A coroner ruled that his death was a homicide, and the prison system fired seven guards and a nurse; two more employees resigned. No criminal charges were filed.

Surveillance video captured much of the guards’ encounter with Mr. McDaniel, who ended up on the ground 16 times over the course of less than an hour. But the video missed several key moments: a stairwell blocked much of the initial fight between Mr. McDaniel and the guards, in which investigators determined that he had punched two officers, and the cameras captured only part of a takedown, several minutes later, in which guards appeared to push him into the snow outside.

Mr. McDaniel’s sister, Jada McDaniel, said she supported the use of body cameras and believed that the guards might have intentionally engaged her brother behind the stairwell, knowing that it partially obscured what was happening. Ms. McDaniel said she believed that the guards would not have been so aggressive with her brother had they all been wearing cameras.

“My brother would still be alive,” said Ms. McDaniel, who teaches math and science to fourth graders in Columbus. “They would have thought twice. They probably wouldn’t have taken him out and abused him the way they did. There’s no way they would have taken him behind the stairwell.”

Ms. McDaniel said she believed that the guards would also benefit from having more of their interactions on camera.

“The guards need protection as well,” she said. “The body camera will catch everything.”

A new prison agency policy governing body cameras says that cameras may automatically activate when a gun or pepper spray is drawn. The policy says that the cameras must be powered on at all times, meaning that even if guards cannot or do not activate them, video would still be captured and stored for 18 hours.

In jails and state and federal prisons across the country, officials have been struggling to hire enough prison guards to fill in for those who have retired, fall ill with Covid-19 or are avoiding dangerous assignments, leaving correctional facilities with high infection rates and not enough staff to handle potentially violent confrontations.

In New York, stabbings at the massive jail complex on Rikers Island have surged and gangs have increased their influence in the jail during the pandemic as some prison guards have taken advantage of generous sick leave policies. Some guards wear body cameras at the complex, but not all.

In 2019, the sheriff overseeing the jail in Albany County, N.Y., said he was putting body cameras on guards after several inmates who had been transferred from Rikers Island said they had been abused at the Albany jail. The sheriff said at the time that he believed the cameras would have proven that the officers were innocent.

Prison officials in several other states, including Wisconsin and Georgia, have begun to put cameras on some prison guards. A lawsuit in California over claims that prison employees had violated disabled prisoners’ rights led a judge to order that officers at five state prisons be outfitted with the cameras. New York State has also tested the technology at some prisons, and New Jersey lawmakers are considering a bill that would put body cameras on every prison guard.

The Ohio Civil Service Employees Association, which represents prison guards in the state, has not opposed the body camera program but said it was a low priority at a time when there were 1,700 vacant positions for correctional officers, in part because the state had not filled positions of officers who had recently retired.

“To be frank, it’s hell right now,” the union president, Christopher Mabe, a retired prison sergeant, said of working in Ohio prisons. “Body cameras are a distraction, as far as we’re concerned, to the real and dangerous staffing issues in prisons now.”

Ms. Chambers-Smith, the prisons director, said the body-worn cameras would cost $6.9 million in the first year and about $3.3 million each year after that. They were being paid for by grants, funding from the federal stimulus act passed by Congress in response to the pandemic in 2020, and the department’s general budget.

Jonah E. Bromwich and Jan Ransom contributed reporting.

Advertisement