From the lecture series: America's Founding Fathers

In America, widespread land ownership opened access to voting rights for unprecedented numbers of ordinary Americans. This was opened still further as state legislatures in North Carolina and Pennsylvania began adding non-landholding taxpayers to the voting roles. Briefly in the 1780s, even free blacks in eight of the thirteen states could vote. By the time of Washington’s re-election in 1792, seven states had jettisoned property-owning as a qualification for voting and, across the republic, as many as 80 percent of white males were eligible to vote.

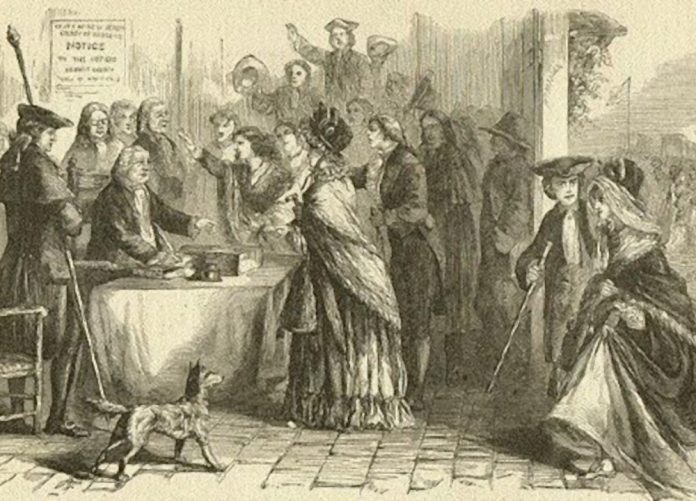

However, one category of free Americans did not have the vote, and that, of course, was American women, the solitary exception being New Jersey until 1807, where women could vote based on property ownership. From time out of mind in hierarchical societies, women scarcely had any independent existence, either socially or legally; married women were legally classified as femmes couvertures, and could not be sued or sue, could not draft wills, or make contracts, or deal in property. Thus, the male head of a household was a miniature king, and a king or a governor or a squire was, by extension, simply a father writ large, with all of Anglo-American society in legal dependence on him.

Learn more about the American republic.

However, the solvent of liberty ate away at this most intimate and traditional restraint. Thomas Jefferson might think that American women were “too wise to wrinkle their foreheads with politics,” but those women thought otherwise. “The Sentiments of an American Woman,” announced a broadside posted in 1779 in Philadelphia, were “born for liberty.”

In law, Abigail Adams complained, married women’s property remained “subject to the control and disposal of our partners, to whom the law has given a sovereign authority,” but that did not stop her from acting as her husband’s business agent while he was abroad on diplomatic missions, nor did it stop her from upbraiding her husband to “destroy the foundation of all pretensions of the gentlemen to superiority over the ladies.”

In a society of political equals, not to mention a republic which was the first offspring of the Enlightenment, marriage itself was the first institution to be reconceived. American women of the 1790s had a far more Lockean set of objectives in view. No longer would men be kings, nor would marriage be a kind of domestic diplomatic arrangement between the fathers of brides. Women began to consider themselves as the partners of their husbands, not their handmaids; and marriage itself was to be built on companionship and affection, rather than the strategic placement of heirs.

This is a transcript from the video series America’s Founding Fathers. Watch it now, on Wondrium.

Judith Sargent Murray, who began a career as a woman of letters in Massachusetts in 1782, when she published a children’s catechism, went on from there to write plays and produce a three-volume set of essays, The Gleaner. Murray predicted that “the equality of the female intellect will never, in this younger world, be left without a witness.”

Mercy Otis Warren entered the fray over the ratification of the Constitution in 1788 with Observations on the New Constitution, and on the Federal and State Conventions, and went on to publish plays, poems, and an ardently anti-Federalist History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution in three volumes in 1805.

The road to equal rights, property, and access to power lay through education. “Female education should be accommodated to the state of society, manners, and government of the country in which it is conducted,” insisted Benjamin Rush.

Whatever Thomas Jefferson’s worries about wrinkled brows, his granddaughter Ellen Randolph, born in 1796, was studying Greek, Latin, French and mathematics by the time she was 10, and offering her grandfather advice on natural history and art.

Learn more about Thomas Jefferson’s books.

Susanna Rowson’s Young Ladies Academy in Boston, the Young Ladies Academy of Philadelphia, Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Academy, and the Quakers’ Westtown School opened their doors in the 1780s and 1790s, and their graduates were not shy about claiming a larger role for themselves in American life.

“A more liberal way of thinking now prevails,” announced Priscilla Mason, in her “Salutory Oration” at the Young Ladies Academy of Philadelphia in 1793, and though presently she said, “The Church, the Bar, and the Senate are shut against us,” there was “nothing in our laws or constitution to prohibit the licensure of female attorneys,” much less the ministry or politics. “Let us by suitable education qualify ourselves for these high departments.”

There is no evidence, however, that Priscilla Mason ever practiced law, and for all the egalitarianism implicit in women’s education and writing, the most talented female poet of the republic, Phillis Wheatley, remained as she put it “a mere spectator” of the new Republic—she was not only female but black, and spent all but the last years of her life in slavery in Massachusetts.

This indicates that the emancipation movement and the process of enfranchisement was still moving slowly during the early American republic and had a long way to go.

In the early American republic, the widespread land ownership opened access to voting rights for ordinary Americans. By the time of Washington’s re-election in 1792, seven states had jettisoned property-owning as a qualification for voting and, across the republic, as many as 80 percent of white males were eligible to vote.

In the early American republic, American women did not have voting rights, with the solitary exception being New Jersey until 1807, where women could vote based on property ownership.

In her “Salutory Oration” at the Young Ladies Academy of Philadelphia in 1793, Priscilla Mason said that there was nothing in the American law or Constitution banning women from being attorneys, ministers or politicians, and so the women should educate themselves and qualify for these departments.

Music History Monday

TGC Blog

Roy Benaroch’s Pediatric Insider

Professor’s Perspective

Smithsonian Articles

National Geographic Articles

Culinary Institute of America

Newsletter Archives

About Wondrium

Wondrium

The Great Courses

Contact Us

Sitemap

Privacy Policy

Terms and Conditions

© The Teaching Company, LLC. All rights reserved.